As a parent of a child with SEND, I must make it clear that I completely disagree with recent comments made by Nigel Farage. His claim that children in the UK are being “massively overdiagnosed” with mental health and behavioural conditions does not reflect the evidence—and it risks adding further pressure to families already facing immense challenges.

At a press conference on 24 April 2025, Farage stated:

“I think we are massively—I'm not being heartless, I'm being frank—I think we are massively over-diagnosing those with mental illness problems and those with other general behavioural disabilities.”

He went on to suggest that these diagnoses are being handed out casually:

“So many of these diagnoses... have been conducted on Zoom, with the family GP.”

And he concluded with a warning:

“I think we’re creating a class of victims in Britain that will struggle ever to get out of it.”

These remarks reflect a serious misunderstanding of how SEND works in this country—and more worryingly, they risk fuelling stigma at a time when families need support, not suspicion.

Let’s start with the claim of over-diagnosis. In fact, national research suggests the opposite. The UK Household Longitudinal Study has shown that individuals experiencing serious psychological distress without formal recognition or access to support outnumber those receiving services without clear clinical need by a factor of twelve. The real crisis in the UK is not over-identification—it is unmet and delayed need.

Identifying SEND is neither casual nor GP-led. Conditions such as autism, ADHD, and learning difficulties require comprehensive assessments from specialist teams. These teams typically include paediatricians, educational and clinical psychologists, and speech and language therapists. GPs cannot and do not diagnose these conditions—they refer families into overstretched pathways that often involve months, or more typically years, of waiting.

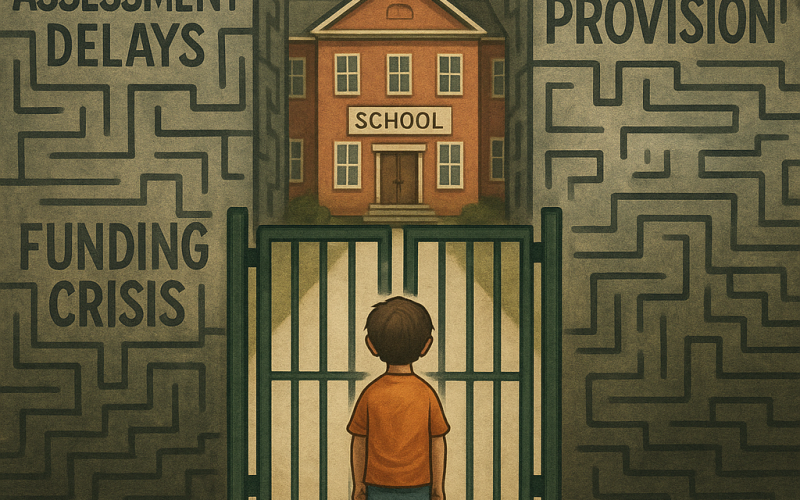

Farage’s remarks also ignore the scale of these delays. According to the Children’s Commissioner (October 2024), more than one in four children who are referred for an Education, Health and Care needs assessment are still waiting over two years later. This is despite the legal requirement to complete the process within 20 weeks. These delays aren’t the result of families demanding too much—they are the result of a system that cannot cope.

Moreover, Farage fails to acknowledge the reality of children who are completely absent from the system. A growing number of children with complex needs are unable to attend school at all. Many experience school-related anxiety, sensory distress, or lack access to appropriate provision. These children are not being "swept into diagnosis." They are falling through the gaps—and their invisibility in political conversation is part of the problem.

The idea that identifying a child’s needs turns them into a "victim" is not only unfounded, it is harmful. Longitudinal research from the University of Cambridge has shown that when children’s needs are properly understood and supported, they experience gains in self-esteem, academic achievement, and wellbeing. What harms children is not recognition—it is denial.

It is true that SEND provision places significant pressure on local authority budgets. But this is not a sign of professional overreach or parental opportunism. It reflects genuine social and demographic shifts: better public understanding of neurodiversity, and a growing refusal among families to accept exclusion as inevitable.

Farage’s remarks reduce a deeply complex issue to a simplistic culture-war narrative. They misrepresent both the nature of the system and the motivations of those within it—parents, professionals, and children alike. In doing so, they risk legitimising mistrust of the very people who are most vulnerable to the system’s failures.

SEND is not about political posturing. It is about children who need understanding, families who need access, and public services that need appropriate funding. If we are to maintain public trust, we must avoid slogans and face the facts. The facts are clear: the system is not too generous. It is not too quick to act. It is too slow, too fragmented, and too overstretched to meet the real needs of the children it is supposed to serve.

Farage is wrong. And if we are serious about evidence, fairness, and integrity, we need to say so !